A brief history of ‘integrated delivery’

The idea of ‘integrated delivery’, as highlighted in the UK Government’s (HMG) 2021 Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy, is not new.

The drive towards cross-government working has been around since the 1990s and became more pronounced with the advent of the National Security Council in 2010. The Fusion Doctrine that came out of the 2018 National Security Capabilities Review drove forward whole-of-government working through a ‘culture of common purpose’. The 2021 Integrated Review (re)visited these earlier concepts and outlined the need for even ‘stronger collective strategy capability’.

Yet, integrated delivery is still not normal practice within HMG. This matters, as, increasingly, HMG will be called upon to respond to challenges of scale and kind not seen before, whether it be the COVID-19 pandemic, climate and ecological crises, or transnational threats.

Integrated delivery as both a strategy and a practice

This blog explores why there is a disconnect between the ambition and reality of integrated delivery, and what can be done about it. It draws on research by Itad, and our partner, Altai, on behalf of the Conflict, Stability and Security Fund (CSSF) team in Jordan which led to an Integrated Delivery Framework and accompanying guide for senior managers.

These tools demonstrate how integrated delivery is both a strategy to be adopted and a process to be implemented. They offer much-needed support to HMG management and programme teams to:

- identify when and why resources should be integrated across multiple departments and stakeholders;

- how to monitor when integration is happening;

- whether it significantly enhances collective capability; and

- understand whether cultural changes in working practices have been achieved.

Why is integrated delivery important?

Integrated delivery has been called for repeatedly since the 1990s and is important because:

- It enhances the operational capability of HMG and supports the delivery of National Security Council (NSC) objectives in high-risk environments.

- The FCO and DfID merger requires new ways of integrated working and cultures.

- In addition to the FCDO, there are 10 other departments within the CSSF alone, who are regularly called upon to respond to complex crises.

- The ‘Global Britain’ agenda is dependent on the resolution of complex social, political, economic, security and environmental issues that no one department can respond to alone. This requires the creation of an environment where innovation can thrive.

If integrated delivery is not new, then what’s holding it back?

Integrated delivery will always be difficult to achieve and, from our research, we identified the following reasons that can hold it back:

- Cultural change is required to embed new ways of working.

- Information sharing is too inward-facing and not shared across HMG and external partners.

- Strategies are not context-specific enough, relying too much on high-level NSC objectives.

- Not enough senior-level buy-in for shared outcomes at country and Whitehall levels.

- Reporting and governance mechanisms, roles and shared responsibilities are unclear.

- Little guidance on good practice is available to guide teams.

So what does good integrated delivery look like?

Informed by observations in Jordan and consultations with HMG staff, we define integrated delivery as:

- Integrated delivery is where joint analysis and strategy development across departments is the norm, not the exception; where collaboration begins with a merging of knowledge and analytical capabilities;

- Integrated delivery is not only about UK cross-government working but includes key boundary partners beyond HMG (see figure 2 below);

- Integration is reliant on a ‘culture of common purpose’ that is deeply rooted in the local context, and where institutional constraints are removed to allow innovation to flourish.

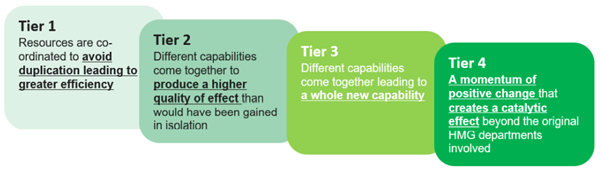

- Integration at a minimum produces an effect greater than the sum of its parts and, at its most aspirational, creates a whole new capability, or a catalytic effect (see fig 1 below):

How do you maximise effect?

Stability, like in Jordan, requires complex social, political and economic responses and we found that integrated delivery in Jordan drew on the capacity and capabilities of traditional government departments including FCO-DfID and MOD, as well as non-traditional departments – e.g. Office for National Statistics, and HM Revenue and Customs. They also worked with a range of partners external to HMG: Jordanian ministries, the private sector, civil society and communities.

Based on an initial review of these examples we made three important observations:

- There was a willingness to work differently within HMG in Jordan;

- There was a breadth and ambition to engage a range of stakeholders within and outside HMG;

- The results achieved were better than expected.

The likelihood of increasing the ‘tiers of effect’, therefore, is linked to a willingness to engage a range of stakeholders and an openness to working differently (i.e. overcoming the challenges listed above that hold integrated delivery back).

An Integrated Delivery Framework

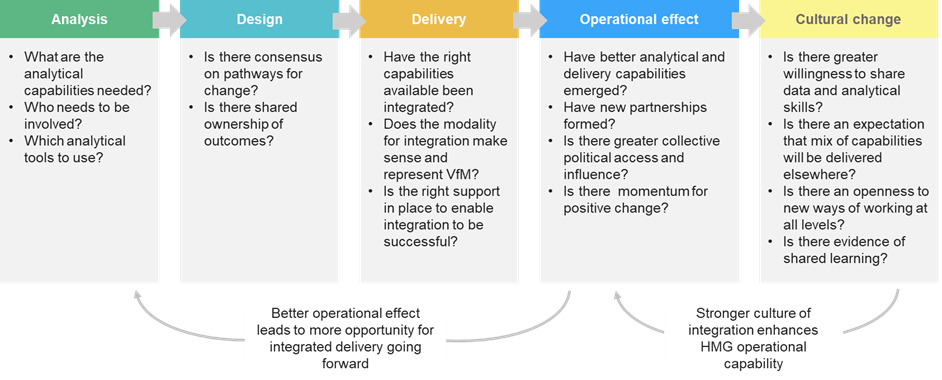

Based on our observations, we developed a framework that could monitor and encourage integrated delivery, aimed at senior managers, to:

- Identify the need for integrated delivery and which HMG resources – internal and external – are needed for the task.

- Monitor whether the right conditions are in place to encourage different ways of working and whether there is an enabling environment to encourage innovation.

- Understand whether integrating capabilities has led to more effective outcomes and catalytic effect.

The framework is structured around key performance questions that can be reviewed at different stages of an intervention cycle:

What next?

Integrated delivery is here to stay!

So we are working on an integrated delivery toolkit. For example, we have developed stability trackers to integrate analytical capabilities across HMG and inform shared strategy development (read our blog on stability trackers). Combined with our work on measuring political access and influence we have an emerging integrated delivery toolkit that we hope to be able to pilot at a country-level within the CSSF network in the coming months.

We are keen to hear from others who may have experience of integrated delivery and to share learning and examples.

We also invite any programme and country teams who may want to learn more about the tools mentioned to contact us.

Contact details: tom.gillhespy@itad.com; georgie@gssinclair.com