When addressing complex societal challenges like those we’re focused on at Luminate, it can be very difficult to pinpoint the causes or solutions. Paths are emergent and non-linear, so a systems-thinking mindset and a holistic approach is critical to effective change and development.

When addressing complex societal challenges like those we’re focused on at Luminate, it can be very difficult to pinpoint the causes or solutions. Paths are emergent and non-linear, so a systems-thinking mindset and a holistic approach is critical to effective change and development.

As part of our 2022-27 organisational strategy development process, we recognised the need for clear systems change objectives. Once we created our strategy, which is focused on ensuring that everyone – especially those who are underrepresented – has the information, rights, and power to influence the decisions that affect their lives, we had a new challenge: how to assess its effectiveness. There is limited consensus on how to effectively measure systems change, so we decided to take a new approach that distils systems theory to produce a practical learning framework.

Bringing causal pathways to the fore

Before the current strategy, we informed our decisions about interventions with a hybrid approach, combining hypotheses with specific objectives and outputs. At the time, that approach often felt unsatisfying because our systems didn’t enable us to consider the complexity of causal pathways. We weren’t having enough of those conversations where you step back from the evidence and ask ‘So what? Now what?’

Measuring systems change is hard. This is perhaps reflected in the limited literature on how to measure systems change within the context of Monitoring, Evaluation, and Learning (MEL) practices. Evaluation methods have been developed in conjunction with systems thinking, but there is little out there that non-evaluation experts (such as members of the wider foundation teams) could engage with.

Our challenge was to develop a means of being explicit about how we could ground our learning in hypotheses and foster a culture of learning. We needed a way to close the learning loop and more efficiently use learning to influence decision making.

Embracing hypotheses and a simple learning framework

We knew that we wanted a new framework that was pragmatic, actionable, and tailored for our small Learning & Impact team. We also wanted a framework that could help us to:

- Achieve ongoing, iterative learning grounded in evidence and experience

- Learn at multiple ‘levels’ – themes, geography, and project levels

- Integrate external and internal points of view

- Allow us to respond to new information quickly.

To embrace this ethos and test a range of interventions with possible outcomes, we developed a Learning Framework that allows us to test uncertainties in our strategy, challenge our team to collect confirming and disconfirming evidence, support our decision making, and help us identify causal relationships.

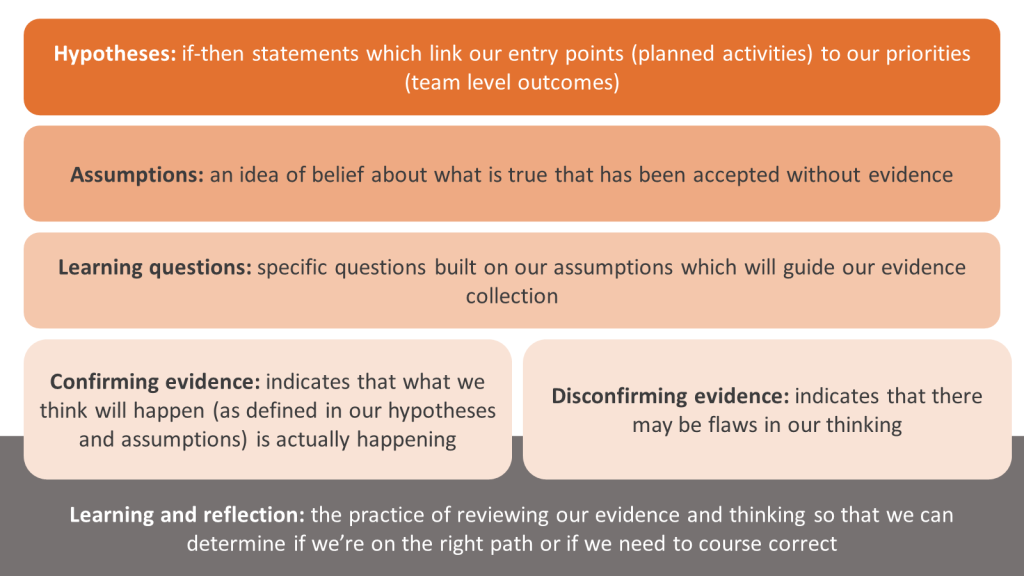

The Learning Framework itself is a simple structure, comprised of core ‘building blocks’ which ensures our evidence collection is focused and leans just as much on reflection and sense-making as it does on gathering evidence. This requires team members to articulate their hypotheses and assumptions while paying close attention to system boundaries and multiple perspectives.

Learning framework components:

There are four “levels” to our framework:

1) Hypotheses: Each of our team’s strategies is distilled into a hypothesis. These are if-then statements which link our planned activities to the outcomes that we are working toward.

2) Assumptions: Teams identify the assumptions (related to cause-and-effect, context, and implementation) that underlie their hypotheses. Teams might come up with dozens of assumptions and we prioritise those which would have the most serious consequences to our strategy if they did not hold up over time.

3) Learning questions: These action-oriented questions, which are built on our prioritised assumptions, help us test and interrogate them and make our evidence collection more effective and efficient.

4) Confirming and disconfirming evidence: We define evidence as an outward sign or indication that something may be true (or not true). Relevant evidence should give us an informed sense of whether our hypotheses and assumptions hold up or need to be revised or rejected.

These framework components comprise the “what” of our learning approach, but it’s important to note that reflection, conversation, and learning are critical to our approach. We have stepped away from having organisation-level key performance indicators and metrics in recognition of the fluid nature of the contexts in which we work. We rely on these evidence-based learning conversations within and across our teams every six months during which we revisit our assumptions and evidence. To ensure we learn from evidence during those opportunities, we ask ourselves what happened, why it was important, and what it implies about our future actions. In short, it means asking ourselves: What? So what? Now what?

Learnings and recommendations for those considering a similar approach

We are now more than six months into implementing our Learning Framework, and we have learned some valuable lessons that may benefit others who are interested in this approach:

- This is deep work. In order to bring this framework to life, we are shifting organisational culture and confronting our assumptions. This requires developing meaningful learning questions and having honest and transparent conversations. It’s framework plus! The framework is a starting point, but it’s about building the learning culture to support it.

- Throw out the jargon. This is important to help teams to turn their assumptions into a learning question that they find compelling and directly linked to decision making. It can get a bit more technical when we discuss the evidence collection plan, but this is where our Learning & Impact team can assist to suggest particular methodologies to help answer the learning questions. We also found it really helpful to have conversations about “what is evidence?” and to discuss the utility of informal as well as formal evidence.

- To support a culture shift, you need leadership buy-in. Our Board have been wonderfully receptive and embraced this kind of learning, and we have incorporated this into our reporting. Members of our Leadership Team were actively involved during our onboarding workshops across the organisation, and they are role modelling and committing to our learning practices. Their commitment is critical to success.

- Confront your biases. Because we are regularly sensemaking, we have to be more aware of the types of cognitive biases that we may fall prey to and to actively look for evidence that confronts those biases. We brought in an advisor early on to help us better understand biases that might hinder us from deep learning. We’d like to continue that.

- It is imperative to constantly consider how the outputs of the learning will be used and by whom. Outputs must be super relevant, accessible, and aligned to the priorities of the organisation.

- None of this precludes undertaking rigorous evaluations, but these will build on what’s gathered under the Learning Framework. For instance, portfolio or organisational evaluations which aim to influence strategic decision making at a slower cadence (e.g., three to five years) can use, augment, and deepen the evidence captured under our Learning Framework.

Catalysing conversations for change

It’s early days for us, but if the framework improves decision making and creates space for constructive conversation to advance our goals, it will become further embedded over time.

Meanwhile, I will look forward to sharing our failures and successes for the wider sector. I also look forward to discussing the approach more in the upcoming panel event hosted by Itad on technical innovations in MEL for systemic change. And I would love to hear from others who are employing similar approaches, so please share your experiences and perspectives by joining the event and contributing your views on the value of a learning framework in MEL to support organisational change.

Kecia Bertermann is Director of Learning and Impact, Luminate