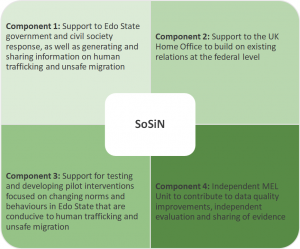

In this blog, I want to share my reflections on SoSiN which was brought to an early close in the second half of 2020 following an overall reduction in FCDO budgets. The programme was originally intended to run between 2019 and 2023 and represented FCDO’s major response to modern-day slavery (MDS). The programme, which fits into the broader UK government response to MDS, was structured around four components that, together, were going to ensure a state-coordinated and evidence-based response to tackling the root causes of human trafficking and unsafe migration in Edo State of Nigeria.

The early closure of the programme has implications. Apart from the potential loss of the small gains that have been made in the first year of implementation, there are in my opinion, five missed opportunities, which I will elaborate below.

1. An integrated approach to tackling MDS

Component 2 of SoSiN is part of the broader UK government’s investment in the Home Office’s Modern Slavery Fund in Nigeria, Albania and Vietnam, in the form of support towards the response of law enforcement and support for victims. The ICAI review observed that the UK’s choice of programming has focused primarily on international trafficking despite evidence that trafficking within the country is an even greater problem in Nigeria. The early closure of the SoSiN programme presents a missed opportunity because the other components were meant to pilot interventions that will test innovative approaches around what works (or not) in combating human trafficking. This evidence would have been useful in designing programmes that can be scaled up to other parts of the country.

2. A government-led and sustainable response

The ICAI review pointed out that UK government programmes in Nigeria have provided valuable support to returnees. Both FCDO and Home Office programmes have provided a range of support through the Institute of Migration (IOM) to over 2,000 highly vulnerable individuals who have returned after traumatic experiences of trafficking – although at a relatively high cost that raises questions about the sustainability of the approach.

The longer-term outcome of the SoSiN programme should have been a coordinated and evidence-based state-level response that tackles the drivers of human trafficking and unsafe migration. This requires strengthening the capacity of government and non-government actors so their approaches tackle the root causes of human trafficking and unsafe migration.

The ICAI review observed that programmes have generally not been selected based on a systematic review of modern slavery in a given country or the priorities of partner governments. The SoSiN programme, however, was conceived in response to the political momentum in Edo state. The Governor, Godwin Obaseki, established the Edo State Taskforce Against Human Trafficking in 2017 to work together with the National Agency for the Prohibition of Trafficking in Persons (NAPTIP). In 2018, the Edo State Trafficking in Persons Law (2018) was signed into law, with three main objectives; namely to provide an effective and comprehensive legal and institutional framework for the prohibition, prevention, detection, prosecution and punishment of human trafficking and related offences in Edo State, to protect victims of human trafficking and to promote and facilitate local, national and international cooperation.

Shutting the programme early means there was a missed opportunity to institutionalise a state-led approach that could have led to sustainable change.

3. Refining terminology to suit particular situations

The ICAI review notes that the term ‘modern slavery’ was included in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) following a strong lobbying effort by the UK in 2015. However, one of the weaknesses of the UK modern slavery approach is that it has treated modern slavery as a single phenomenon when its elements are extremely diverse.

Stakeholders involved in the ICAI review highlighted that there are specific issues such as safe migration, trafficking and poor working conditions and that the term is disliked by people in some countries because it is embedded in the historical, colonial and military rule context.

This perception was evident in Edo State when SoSiN started. Arising from the interactions with stakeholders and the need to be aware of sensitivities on the use of the term “slavery”, the main implementation component (Component 1) adopted Stamping out Trafficking in Nigeria (SoTiN) as nomenclature. This was also in order to fit into the contextual issues in Edo State, and to ensure better alignment with the government response, and hence achieve better traction in relationships. With the early programme closure, it seems like a missed opportunity to help refine terminology and unpick and clarify issues coming from stakeholder engagement as part of the implementation. This would have fitted into the programme ethos of generating lessons that can be shared nationally and globally.

4. Leaving no one behind

The ICAI review alluded to a lack of survivor voice in terms of research, and in terms of informing programme design. An important component of the SoSiN programme is a challenge fund to CSOs to design innovative programmes. Due to the early closure of SoSiN, there is a missed opportunity as many of the CSOs that would have been potential beneficiaries of the challenge fund are staffed by returnees. These are people who have first-hand experience and who could have helped construct and build the narrative on MDS, and this way inform future programme design.

5. Contributing to the evidence base

Finally, the ICAI review expressed concern about the lack of robust theories of change for modern slavery programmes managed by the Home Office and the FCO. The failure to articulate clear causal pathways and identify measurable outcome indicators has meant that the capacity of these programmes to generate useful results data has been weak. In the context of a new and complex area of engagement, pilots are only useful if they provide a high-quality platform for learning.

The early closure of SoSiN is a missed opportunity because SoSiN’s implementation was predicated on a robust theory of change which would have generated evidence on what works or does not.

There is also a lost opportunity for longer-term engagement on the issues of MDS which requires long term change.

The review also observed that the federal government of Nigeria signed up to the 2015 Sustainable Development Goals’ international Call to Action and offered to be a regional leader within West Africa. Some state governments in Nigeria have acted under the Call to Action, but there has been little follow-up or reporting at the federal level. Edo State is probably the only state that has enacted state law against trafficking and SoSiN lined up behind the strategy. This was an important opportunity, and the approach of SoSiN would have contributed to generating information that is joined up with other initiatives at the federal level.

Going forward

While there have been several missed opportunities arising from the early closure of the programme, there is much that can be learned from SoSiN’s implementation to date.

A lot of the analyses that have been undertaken across the component projects suggest that poverty is the largest factor driving human trafficking and unsafe migration.

FCDO can use their relationship with the state and federal government on the one side, as well as other programmes working with civil society, to advocate for livelihood support to individuals prone to human trafficking through the provision of employment opportunities, income-generating activities, seed grants, training and scholarship. This would hopefully address the majority of the root causes and reduce vulnerability to human trafficking and unsafe migration. With a high proportion of younger people being at risk, there should be a special focus of the support on these age groups.

There is also a knowledge platform that is being developed by component 1 of the programme. All of the knowledge generated so far will be placed on the platform and handed over to the government or non-government organisations, so it becomes part of the existing platforms for collaboration, which is focused on knowledge sharing.

The ICAI report certainly resonates with my experiences in Nigeria of addressing modern slavery. While there have been several missed opportunities, we are keen to share the knowledge generated with the hope that others will gain insight from evidence around modern slavery.

Take a look at the summary of the key findings from the SoSiN baseline assessment, and read my previous blog sharing lessons.