Philanthropy is confronting crisis and opportunity

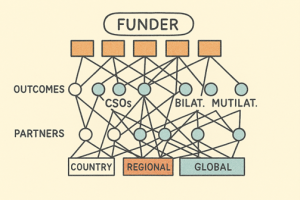

Foundations operate in complex, dynamic systems, where new threats and opportunities constantly emerge. Navigating these systems and deploying scarce resources for maximum impact is challenging at the best of times – perhaps even more so now, given the retrenchment of domestic and international aid programmes in 2025 and the resulting surge in demand for philanthropic support to fill gaps in social impact spaces. This challenge is amplified as more philanthropies shift toward portfolio-level approaches.

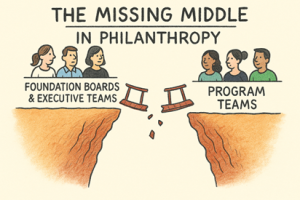

At the same time, philanthropies – especially those pursuing collective impact through funding portfolios rather than simply supporting discrete projects – face internal dynamics that are equally complex. Boards and executive teams need to be able to exercise high-level oversight and govern resources for long-term impact without getting lost in operational details. Meanwhile, programme staff need to monitor contexts, assess progress towards intended outcomes, and adapt short- and medium-term strategies in near real time. These roles require different types of information, creating a ‘missing middle’ between boards and staff.

Traditional monitoring, evaluation, and learning (MEL) approaches often fail to meet either set of needs, leaving boards and staff talking past one another – to the detriment of their organisations and the communities they aim to serve.

Mind the gap: consequences of the ‘missing middle’

The missing middle is understandable. Portfolios and complex systems can be hard to make intelligible. They involve diverse partners, often across multiple contexts, numerous projects and approaches, and often span multiple levels – local, national, regional or global – and sectors.

But the gap it creates has real consequences: the missing middle can obscure shared line of sight between staff and boards, raise the risk of miscommunication and misalignment, and ultimately undermine cohesion, effectiveness, and impact – harming philanthropies, their partners, and most importantly, their missions.

So what does it take to bridge this gap? How can philanthropies manage portfolios for impact, while collecting and using information that meets the distinct needs of boards and staff? How do we understand individual results while assessing collective contribution – positioning boards and staff to work together as they navigate and shape complex systems?

Closing the gap: principles for aligning boards and staff

We’ve worked with many partners grappling with these challenges, including non-philanthropic partners (see, for example our recent work with Norad). There is no ‘one size fits all’ approach to portfolio-level strategy and learning – no single way through which to plug the missing middle. Organisations need bespoke approaches tailored to their contexts and aligned with the priorities of both boards and staff (for example, in recent years, the Ford, Hewlett, and Rockefeller Foundations have each launched different approaches to developing and managing portfolios). But where to start?

Our experience suggests four guiding principles can help. Applying these principles in ways that are suited to particular contexts enables philanthropies to collect and use evidence, and chart a course for learning and impact that supports all stakeholders.

1. High value, not high volume

Don’t try to assess everything in a portfolio. Focus on the elements that deliver the greatest strategic value.

MEL efforts, especially portfolio-level MEL efforts, should centre on informing the key decisions – short- and long -term – that portfolio managers need to make. Resources for MEL – including time and attention – are limited. You can’t learn everything about the portfolio – and you don’t need to. Instead, identify decision points upfront and drill down strategically into the key questions, hypotheses, and assumptions which most need clarity. This approach surfaces the evidence and insights that boards and staff can use to make decisions that drive impact at both governance (board) and portfolio/programme (staff) levels.

2. Tapestries over metrics

Weave together different types of evidence and stories to craft crosscutting insights and patterns.

Single indicators – or even aggregated metrics – are insufficient for understanding broad and deep portfolios or systems change. Instead, combine multiple types of evidence and methods, incorporating varied perspectives and ways of knowing. Looking across sources enables you to craft stories of change and identify and validate patterns about what worked, what didn’t, and what needs to shift across the portfolio. Done well, these tapestries resonate with boards (who need the big picture) and staff (who need actionable detail for grantmaking decisions).

3. Contribution for credibility

Assess whether, how, and under what conditions portfolios are contributing to change, rather than seeking to prove attribution.

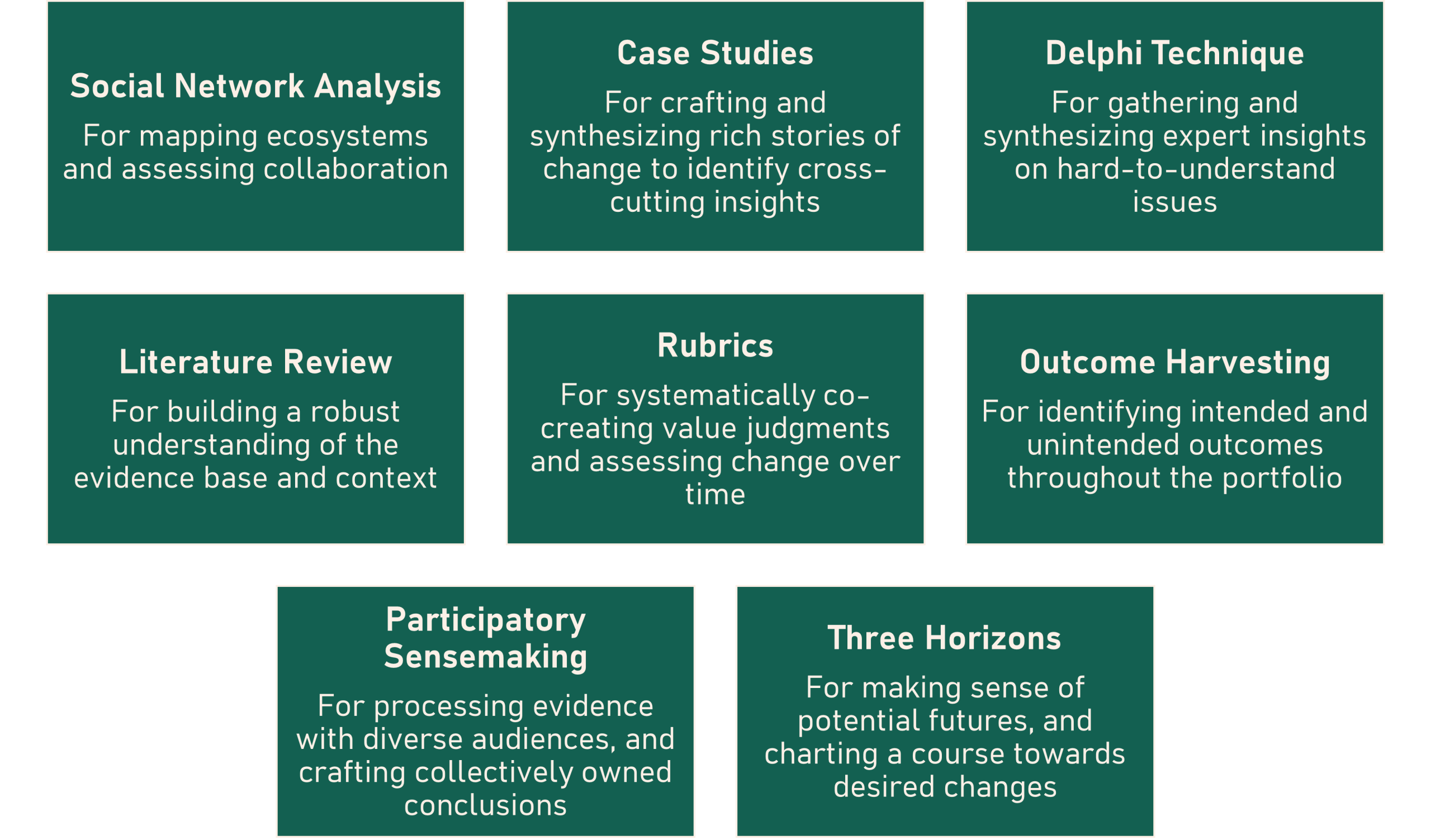

Complex systems involve numerous interacting, dynamic, and emergent variables. Attempting to isolate attribution is not only costly and inefficient but rarely useful. Standardised indicators are often ill-suited to these contexts. That doesn’t mean we throw up our hands and conclude we can’t know whether a portfolio is shaping a system. Instead, philanthropies need to strategically select, adapt, and apply inclusive, rigorous methods that help boards and staff understand not just what changed, but why, how, and in what context.

The graphic below, drawn from recent work with a client, illustrates how different methods and approaches can support this effort. Note that this is an indicative menu of approaches, and not every portfolio would use all, or even many, of these approaches. The key is to select, combine, and adapt methods to fit the specific learning needs and priorities of each portfolio.

4. Sharing line of sight: collaborate to make sense of evidence, draw insights, and take action

Strategically bring staff and boards together to workshop challenges, dig into evidence, and co-create action plans.

Boards and staff often operate in silos, interacting only during infrequent board meetings – sometimes just once or twice a year. This lack of regular engagement means they rarely build the personal relationships and trust that underpin effective strategic learning. They may not even share a common language or understanding of what the philanthropy is doing.

Bringing boards and staff together is not always easy. But creating right-sized opportunities for collective sensemaking – whether through joint sessions or at least collaborative reviews of evidence – can foster trust and alignment. These interactions help both groups converge on shared questions, key lessons, and perhaps most importantly, how to explore those questions and apply emerging insights. This alignment is critical for deciding where to go next, together.

Where do we go from here?

It’s more incumbent than ever that philanthropy meets the moment. That means closing the missing middle and ensuring boards, programme teams and partners work together to maximize, not fragment, their effort towards collective impact. Moving beyond isolated interventions and embracing portfolio-level strategies that reflect the complexity of the systems we want to change is essential.

Strategy and learning professionals are uniquely positioned to contribute to this shift by embedding inclusive, adaptive, and systemic approaches into how we support partners. Let’s build the practices and systems needed to fill in the missing middle, enabling boards and staff to collaborate more productively and achieve lasting impact.