Itad recently undertook the year 3 evaluation of the Pacific Women Shaping Pacific Development (‘Pacific Women’), a 10-year AU$ 320 million programme funded through Australian Aid, working in 14 member countries of the Pacific Island Forum. The programme operates through strategic partnerships and funding relationships that aim to improve the political, social and economic opportunities for women. The formative evaluation took place after approximately four years of implementation and was an independent assessment of whether Pacific Women achieved its first interim objective and to establish the extent to which the programme is tracking toward achieving its intended outcomes.

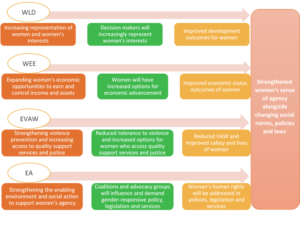

There are four outcomes for the project:

- Women, and women’s interests, are increasingly and effectively represented and visible through leadership at all levels of decision-making (WLDM)1.

- Women have expanded economic opportunities to earn an income and accumulate economic assets (WEE)2.

- Violence against women is reduced and survivors of violence have access to support services and to justice – ending violence against women (EVAW)3.

- Women in the Pacific will have a stronger sense of their own agency, supported by a changing legal and social environment and through increased access to the services they need (EA).

Interactions between WEE and VAWG

Source: Evaluation report. Click to enlarge.

The overall approach for this evaluation applied a theory-driven evaluative process and so was based on a programme theory of change (please see fig 1 for simplified programme logic). A key feature of Pacific Women’s theory of change embeds an assumption that something is to be gained from simultaneous work on all the outcomes. In other words, it is their co-existence which promises overall impacts; and therefore, they need to be activated alongside each other. The evaluation Interrogated and tested the theory of change, so as to understand and elaborate the causal pathways and assumptions. This process revealed a number of interactions between VAWG and WEE.

- Despite the Pacific region being vast and culturally diverse, Pacific Island countries and territories face many common challenges in addressing gender inequality, with violence against women and girls being the greatest of these challenges. For example, a study conducted by the Fiji Women Crisis Centre (FWCC) found that overall, 72 percent of ever-partnered women experienced physical, sexual or emotional violence from their husband/partner in their lifetime, and many suffered from all three forms of abuse simultaneously4.

- One of the major approaches of the Pacific Women project is centred on enhanced knowledge and evidence that informs policy and practice, particularly in addressing women’s economic disadvantage and facilitating greater economic inclusion in contexts where violence against women is high. This approach also draws on work with partners in areas considered to be “red flag” in terms of violence. In these areas, a combination of low levels of education, very low incomes and high levels of poverty, substance abuse and drinking are major drivers of violence.

- There is a recognition that women are in business, but 80% are in the informal economy. Thus, a major focus of the WEE work is about getting women into the formal economy – helping with bank accounts, access to credit and legal protection. So, it’s about entrepreneurship and allowing women to move up on the value chain. Among other things, support for WEE covers initiatives such as financial inclusion for women which includes financial literacy, vocational skills training and linkages to jobs, as well as how to set up own businesses after skills acquisition. There is also the focus of mainstreaming VAWG into “spaces” – markets, skills acquisition centres and training centres; including training on “positive thinking” and counselling. In such “spaces”, there is counselling for women who have experienced violence. From time to time, the police and social welfare services are invited to talk about violence in terms of how to prevent it and how to refer cases.

- The programme provides support for “safe houses” – which provides temporary accommodation for women and children that have been exposed to violence and abuse. Such houses often adopt a case management approach, which involves counselling and providing linkages to legal services. These houses work with other institutions like hospitals, police and courts, who provide referrals such as rape and extreme physical assault. Integral to safe houses is the repatriation programme, which provide support to women who think they can no longer stay in abusive relationships. The programme provides skills in business and related fields, including start-up business kits for those being repatriated. There is regular follow up undertaken by the programme to ensure participants are up and doing. In other instances, participants are linked up with institutions like churches, who then take up their case.

Conclusions

Evidence from the evaluation suggests that the programme is adopting a broader approach centred on the family as a vehicle for dealing with some of the root causes of violence. In PNG, for example, it is dubbed ‘family and sexual violence’, and it seeks to ensure that other violence that is seen in families (such as incest, brothers or fathers beating up sisters and daughters, or even honour killings) do not fall through the cracks. Focus also includes changing attitudes on myths surrounding violence such as women thinking it is okay for their husbands, brothers and fathers to beat, rape and even murder them; or the very low status of women which results in a lack of interest from parents to make sure their daughters have opportunities; or women making excuses for the violence seen in the home, and blaming it on culture or alcohol and drugs.

This family approach is laudable and should tackle some of the interconnected issues of violence and economic empowerment of women. If women and girls are seen to have a better status, then there is a likelihood that parents, especially fathers, will invest more in their girl children and hence better opportunities in the future. It also sits well with the need to continuously document qualitative evidence that the programme inputs are indeed resulting in changes in people’s lives at community level. This is a necessary part of the evidence picture to be confident in the causal processes implied by the programme ToC.

Although violence against women is high in the Pacific and hence programme skewed towards EVAW, there was good consensus that the four intended outcomes of the ToC apply well to the Pacific contexts and, alongside gender mainstreaming, have good potential to generate change – especially when there are links between them. The evaluation recommended that there should be activities in all outcome areas in each country: this will maximise the potential for positive linkages – the co-existence of progress in all outcomes enabling women’s empowerment – to drive the overall impacts of the ToC.